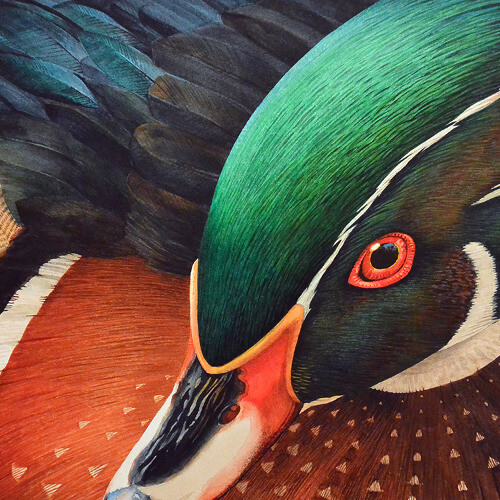

The eye of the duck

One of the tricky things in playing works for violin alone is there isn’t anyone else to sync up to. This may sound like plus, not a minus, but I find that a certain rhythmical laziness creeps in when presenting this chunk of the repertoire.

One solution to this, is just to embrace the luxury and play rubato all the time. And this is what most of us do; and not just fiddle players. Even the great Glenn Gould can be heard bending the tempi quite a bit.

However, to deny this luxury is a bit of an art, and few pull it off with any success. The gold standard for those who do, of course, would have to be pianist Sviatoslav Richter. His approach is ideal, and one to study carefully.

Hanging hats

David Lynch talks about the ‘Eye of the Duck.’ As a painter, he says that when you look at a picture of a duck, the eye, relative to the rest of the duck, is the busiest.

In contrast, in film, the ‘Eye of the Duck’ means something quite different. Lynch stresses that the eye is a moment, a nugget, where the film presents a single image or contained scene that holds tremendous visual power. (Errol Morris alludes that this is pivotal in making a fine film, by saying, there aren’t any great films, there are only great images.)

In interpretive arts, we can hang our hat on this notion by saying that certain passages are incredibly busy. They could be busy technically, or musically. But either way, a piece typically has just one, and here’s where ‘Eye of the Duck’ can be shoehorned to help us out.

Richter

If you listen to Richter play, there’s no moment where he slows down because a passage is too busy. When other musicians would stretch a passage via rubato, or worse, dart through it like some conservatory brat, Richter presents these prickly passages constrained and unblemished. There’s something energetic about this, as our ear gets an opportunity to absorb all that’s going on.

This all comes at a cost, though. It’s one more thing we have to solve before our performance. If the passage is technically tricky, the tempo for this single section has to be discovered in advance. And finding the right tempo is not easy. We must find a tempo that makes it brilliant, but not ‘whipped up’ whereby the listener says to themselves: ‘Wow! Bravo! That was entertaining.’ In contrast, if this passage is played too carefully, it sounds too sleepy.

This ‘Eye of the Duck’ tempo needs to dictate the business of the rest of the piece, tempo-wise. If the eye has tempo ‘X,’ then it follows that the rest of the piece should adhere to this tempo as well, no matter how sleepy that makes some other areas. (Of course, some measure of agogics throughout can generally solve this problem.)

The non percussive instrument

Violin has a much different essence than piano. It’s a cantilena instrument, not a percussive one. Its quality is singing, not rhythm, like keyboards.

However, it’s just lazy to fall into a wash of playing rubato all the time. Moreover, when playing solo works, there’s no end to how much we can slow down to make room for tough technical passages.

By finding the ‘Eye of the Duck’ moments in each work, we can judicially martial the apt tempi so that the glorious moments are more profound, and there is some pacing architecture in place for the music that surrounds such moments. As hard as it is, if we can put this strategy to work, the music we present can become even more impactful.